Definitions

| Open Pedagogy – An approach to education which focuses on free access and learner participation in shaping educational structures and processes. (What is Open Pedagogy?, n.d.) |

| Open Educational Resources – educational materials that are freely available and allowed to be reused, revised, redistributed, remixed, and retained (What is Open Pedagogy?, n.d.). Open Textbooks and Open Courseware are Open Educational Resources. |

| Constructivism – A learning theory in which learners make their own meaning through personal experience and reasoning. (Bandura, 1971) |

| Creative Commons – A non-profit organization that develops and releases licenses for free and open materials (Bliss & Smith, 2017) |

Open Pedagogy

Recall that in Blog Post 2 we discussed Pedagogy, the art of teaching and the science behind its methods (Hotchin, 2025). Open Pedgagogy places students firmly in the centre of the learning process, in charge of what and how they learn, and assuming the responsibilities of being empowered participants in a community of creators and sharers of knowledge. Foundational to Open Pedagogy are the values of autonomy & interdependence, freedom & responsibility, and democracy & participation. (What is Open Pedagogy?, n.d.) This approach expects students to contribute to a communal pool of knowledge, thoughtfully adding to it, asking questions, reflecting and creating from it, and offering respectful critique.

What, then, are teachers in this way of learning? Traditionally, educators take on the role of the experts, imparting knowledge and attempting to have learners retain it. Students might be expected to receive this knowledge without question. They are dependent upon teachers to tell them what to know or where to find information, what to think, and how to apply it. In traditional teaching, lectures, memorization, and skill drills are key methods.

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.com.

In contrast, teachers who use an Open Pedagogical approach might create spaces such as wikis for students to collaborate. A key role for teachers might be to guide students to hone questions, learn to assess their own work, and gain skills in order to increase their ability to learn independently. Part of a teacher’s job might be to help students develop their empathy, see their impact on peers, and understand their power to co-create knowledge within a community. Structures such as learning outcomes, grading rubrics, and course policies can be co-created with a classroom community.

Watch the video below to explore David Gaertner’s thoughts on how to engage students with Open Dialogues.

Open Educational Resources

The Open Pedagogy values of collaboration, connections, diversity, and democracy (What is Open Pedagogy?, n.d.) are well supported by Open Educational Resources (OER). With anyone being allowed to reuse, revise, and remix content, learners can freely share materials, add their own experiences, and bring different content together in original or targeted ways. Not only does this allow students to select information that is relevant to their immediate needs, but in my experience, the act of choosing material and creating with it helps students to understand information more deeply. Perhaps of greater impact, freely accessible Open textbooks reduces the cost of education and Open Courseware reduces the cost further (What is Open Pedagogy?, n.d.). Hewlett, an early supporter and advocate for Open Educational Resources (OER), seeks to achieve OER which are openly licensed, editable, and accessible technologically and by diverse populations (Bliss & Smith, 2017).

Such freely accessible resources would mean a greater ability to bring into class materials that are up-to-date and relevant. Imagine, for example, being able to use a graphing unit built around data from the Covid-19 pandemic while the event was still fresh in students’ minds. Teachers would be able to use what was locally relevant, remix it with their own course content, adapt and refine assignments, and share it back into the educational community.

Access to free resources also means a greater ability to adapt to the needs of students with divergent needs. I know of many schools around the Metro Vancouver area, for example, that use IXL to support students who need additional practice in Math skills and Khan Academy to enable students to explore topics beyond the scope of their courses. I have had experience with elementary school students who have been able to access advanced topics through Coursera.

One of the results I have witnessed of students sharing and creating with OER is the development of skills around digital literacy. They learn to critically evaluate the information they encounter and find multiple sources to back up claims. Students learn relatively early (middle and high school) how to cite sources and they come to respect the work of others.

Another change I have seen as the educational landscape in BC has embraced more constructivist approaches is the increase in the openness of students’ minds to learning from people of all abilities. This welcoming of participation increases engagement and supports a wider variety of communication formats, increasing accessibility for learners. OERs are one more way for students to construct knowledge within a learning community.

Global Trends in OER

In “A Brief History of Open Educational Resources,” Bliss and Smith (2017) describe how countries and institutions around the world are embracing Open Educational Resources. Key events include

- 1993 – Open Access is founded

- 1997 – California State University creates MERLOT to curate mostly free online curriculum materials for higher education

- 1998 – David Wiley from Utah State University proposes a license for free and open content

- early 2000s – OpenStax (a.k.a. Connecxions) develops over 20 open college-level textbooks. MIT opens OpenCourseWare

- 2001 – Creative Commons is founded

- late 2002 – the Hewlett Foundation focuses its efforts on providing Open content

- 2006 – a review of the OER program by Atkins, Brown, and Hammond recommend that the Hewlett Foundation “shape a new culture of learning.”

- 2004 – 2010 Many Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are produced.

- 2014 – Twenty-five countries have clear policy support for OER development and use

- 2016 – the Hewlett Foundation’s strategy is focused on strengthening infrastructure, such as Creative Commons and research, and solving socio-economic problems, such as equitable access to education

Since 2016, the OER movement has continued to grow, allowing access to education for children and youth in prison or foster care, from low-income families, or in government schools in the United States and creating educational opportunities for developing countries Bliss and Smith (2017). A vision that stands out to me is the use of OERs in training professionals, particularly in the developing world. In countries where access to technology, equipment, and specialized environments are limited, virtual laboratories, diagnostic rooms, and operating rooms could allow for medical training that might otherwise be impossible. Additionally, local training supported by local mentors ensures that medical professionals learn in the context of their communities and home cultures. This application of OERs would increase equity in education and healthcare.

A challenge to use of OERs in this way might be access to computer and electronic technology. One way to address this difficulty might include material support from developed countries. Another could be ways to access educational content offline and without electricity, as developed by the Foundation for Learning Equality (Bliss & Smith, 2017).

An additional challenge to the general use of OERs in education, as Bliss and Smith (2017) point out, is the lack of knowledge about OERs by many teachers and professors. However, this knowledge is increasing as social media has aided the sharing of OERs within the education community. Platforms such as Desmos Classroom allow teachers to build original content or modify existing activities and are more and more frequently being used.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons (CC) licensing enables teachers to responsibly use images, music, video, and other educational resources responsibly. Understanding the different types of CC licenses ensures that we abide by any restrictions put on the use of the content. Below are six license types, listed from most to least permissive:

- CC BY – Users may reuse, redistribute, remix, adapt, and add to the material, as long as attribution is given to the creator.

- CC BY-SA – Users can reuse, remix, adapt, and build upon the material, with attribution, but any modifications must be licensed under identical terms.

- CC BY-NC – Reusing, remixing, adaptations, and building upon the material is allowed, with attribution, as long as it is for non-commercial purposes.

- CC BY-NC-SA – Reusing, remixing, adaptations, and building upon the material is allowed, with attribution, for non-commercial purposes, as long as modified material is licensed under identical terms.

- CC BY-ND – Copying and distribution of material is allowed without adaptations, as long as attribution to the creator is given. Commercial use is allowed.

- CC BY-NC-ND – Same as CC BY-ND, except that commercial use is not allowed.

(About Creative Commons, 2023)

Creators may also choose to give up their copyright and allow reusers to use and adapt their works with no restrictions. To do this, they apply a Public Domain Dedication, CC0. (About Creative Commons, 2023)

Applying Open Pedagogy

Use of Open Educational Resources and understanding Creative Commons and Open licensing are helpful to teachers who seek to apply Open Pedagogy to their own practices.

To guide us as we evolve our teaching approaches, we can consider attributes key to Open Pedagogy: participatory technology, innovation and creativity, sharing of ideas and resources, reflective practice, openness of and trust between people, a connected community, learner generated content, and peer review (Hegarty, 2015). For my own classroom, it is useful to recognize the attributes that are also important in the Building Thinking Classrooms approach and the First People’s Principles of Learning.

To create an environment in which students are willing to openly share ideas and resources when problem solving and studying, I need to build a connected community, where students get to know people beyond their personal friends. I am transparent with this intention and ask the classroom community to participate in co-creating behavioural expectations, including suggestions for ways to show support, respond to mistakes, add to ideas, and include others. We get to know one another through structured and informal activity, and practice respect for differences in thinking, history, and identity. The collaboration with others in randomly formed groups to work on sometimes ill-defined problems gives students opportunities to share ideas. The practice of generating class notes using learner generated work encourages a student-centred mindset, as does directing groups who feel stuck to confer with other groups who have found successful pathways. Working with learning outcomes that are openly shared, students reflect upon their learning, classroom experiences, and ways in which their education supports themselves and their personal communities.

Online, I am interested in the practice of using technology such as Google applications to create collaborative notes and share resources. Perhaps this works best in small groups to reduce clutter and allow more opportunities for each student to contribute. Whiteboard applications or online journals could be platforms for collaborative problem solving, while student-created websites could be ways to organize ideas and resources.

In these ways, students are more active participants in their own learning. They are also more aware of others in the learning environment. Providing different ways to collaborate increases accessibility to participation and engagement. As a result, the learning environment is more inclusive.

References

About CC licenses. Creative Commons. (2023, September 28). https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/

Bandura, A. (1971). Social Learning Theory. https://www.asecib.ase.ro/mps/Bandura_SocialLearningTheory.pdf

Bliss T. & Smith M. 2017. A Brief History of Open Educational Resources. In: Jhangiani R. & Biswas-Diener R (eds.), Open. London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc.b

Building Thinking Classrooms: Teaching Practices for Enhancing Learning Mathematics. BTC Site. (n.d.). https://www.buildingthinkingclassrooms.com/

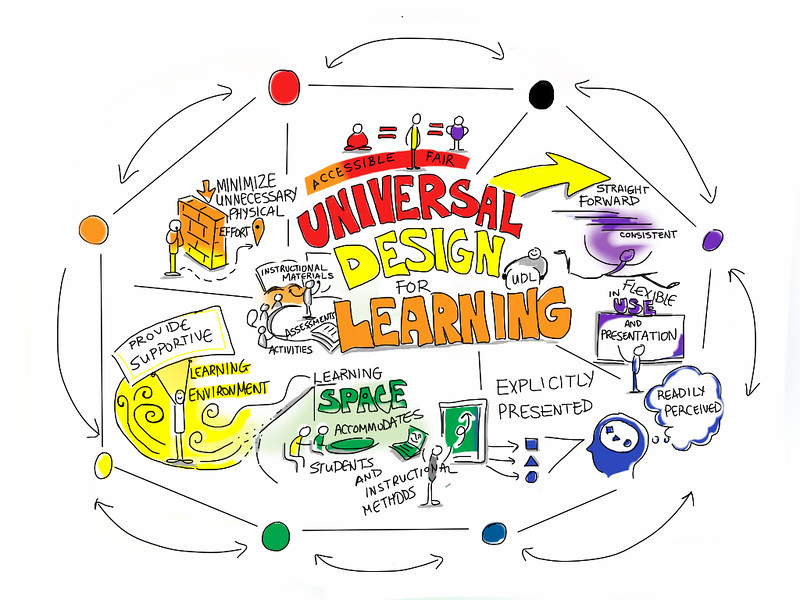

CAST. (n.d.). Universal Design for learning|Cast. Universal Design for Learning. https://www.cast.org/what-we-do/universal-design-for-learning/

Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Technology, University of British Columbia. (2018, January 29). Open Dialogues: How to engage and support students in open pedagogies. YouTube. https://youtu.be/PGVzKqvKhQw?si=rU7dxCUmAyESB3Um

FNESC. (n.d.). First People’s Principles of Learning. First Nations Education Steering Committee. FNESC. Retrieved March 11, 2025, from https://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/.

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of Open Pedagogy: A Model for Using Open Educational Resources. Educational Technology, 55(4), 3–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44430383

Hotchin, J. (2025, January 5). Edci 339 (A01) module 1 – University of Victoria – EdTech. University of Victoria – EdTech. https://connectedlearningpathways.ca/category/edci-339-a01-module-1/

What is open pedagogy?. Open Pedagogy Notebook. (n.d.). https://openpedagogy.org/open-pedagogy/

Recent Comments